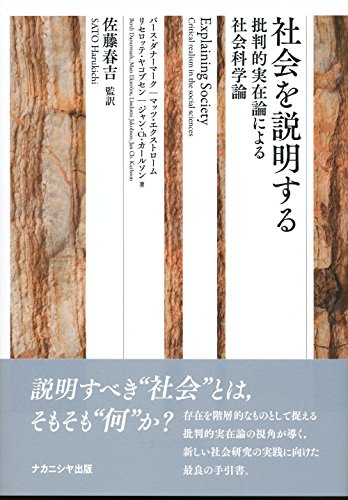

読書ログ:B. ダナーマーク他著『社会を説明する:入門・社会科学の批判的実在論』

原則として英語版(こちらもスウェーデン語から翻訳)に依拠していますが、日本語訳版(下記)も参考にしました。

Chapter 1: Introduction

概要:批判的実在論 (CR) を理解することで、次のような点の重要性が理解できるようになるはず (pp. 1-3)。

- . 科学における適切な一般化の意義

- . 因果関係への焦点化の重要性

- . 「説明」という作業におけるアブダクションおよびリトロダクションの有効性

- . リサーチにおける理論の意義

- . 異なる方法論を併用・統合するうえで不可欠な存在論・認識論への考慮

- . (量的/質的という二分法に代わる)インテンシブ/エクステンシブなデザインという分類

- . 社会現象を「開放システム」と見ることの意義。→そうすることで自然科学的な「予測」ではなく、因果メカニズムの解明に焦点を当てられる。

Some unhappy dualism

理論/メタ理論の位置づけ。そしてその帰結としての法則定立的 (nomothetic) アプローチ vs. 個性記述的 (idiographic) アプローチ

The metatheoretical discussions that have influenced social science have to a large extent been about the role of theories in research practice. (p.3)

過去、方法論をめぐる議論で支配的だった「不幸な二分法」を乗り越えるため、「存在論→方法論→社会理論・実践研究」という3つの概念をきちんとおさえるべし。

The emergence of critical realism

批判的実在論における2つの転回 (p.5):「認識論的哲学から存在論的哲学へ」「出来事中心の存在論からメカニズムへの焦点化へ」

存在論的問い

‘what properties do societies and people possess that might make them possible objects for knowledge ? ’ (Bhaskar, 1978)

To switch from events to mechanisms means switching the attention to what produces the events---not just to the events themselves. Reality is here assumed to consist of several domains ( to which we will return in Chapter 2 ). One of these is that of mechanisms. These mechanisms sometimes generate an event. When they are experienced they become an empirical fact. (p.5)

Critical realism versus foundationalism and anti-foundationalism

二十世紀前半までの素朴な基礎づけ主義 → 実在論の危機。

Foundationalism

a fundamental error : reality is reduced to what can be perceived by our senses. Ontology is reduced to epistemology. (p.8)

Anti-foundationalism

20世紀前半に沸き起こった(西洋的)理性に対する根本的懐疑。そこに触発された反基礎付け主義

Rorty replaces an epistemological fundamentalism with a contextual fundamentalism. The logical consequence of this position is an anti-theoretic relativism. (p.9)

ただし、批判的実在論者としては、、ローティのように、科学的現象を言説レベルに還元すること受け入れられない。

批判的実在論は、(単なる折衷ではなく) 基礎づけ主義と反基礎づけ主義を適切に統合し、既存の科学哲学的紛争を「調停」することができる(というかなり大胆なアピール――要約者)

critical realism claims to be able to combine and reconcile ontological realism, epistemological relativism and judgemental rationality ’ ( Archer et al. 1998 : xi ). (p.10)

Outline of the book

・・・

Chapter 2. Scienece, reality and concepts

「知識」と「知識の対象」の分離。そして、両者の性質の区別。

We start by looking at the relation between knowledge and the object of knowledge. This brings us to the statement that reality has an objective existence but that our knowledge of it is conceptually mediated : facts are theory-dependent but they are not theory-determined. (p.15)

Knowledge and objects of knowledge

「(科学的知識だけでなく)科学的リアリティは社会的に構築されている」とするラディカルな見方に対する異議申し立て→ objects of true knowledge のリアリティへの信頼は維持すべし

Realism maintains that reality exists independently of our knowledge of it. And even if this knowledge is always fallible, yet all knowledge is not equally fallible. It is true that facts are theory-dependent, but this is not to say that they are theory-determined. (p.17)

What must reality be like to make the existence of science possible?

リアリティは自律的であり、社会的に構築されていない。その証拠に、私たちはリアリティを完全にはコントロールできないし、特定のリアリティに関する私たちの知識はしばしば誤りを犯す。

An experiment

オットー・レーヴィ(ノーベル生理学・医学賞受賞者)による、シナプスの情報伝達に関する蛙の心臓を用いた実験を話しの枕に: →知識そのものは、「知識の対象」を操作(=実験)することで、はじめて観測できる

The three domains of reality

リアリティは、直接観測可能な「透明なもの」ではない。科学的実践(実践としての科学)の力によって、そしてリアリティに内在するメカニズムの力によって、ベールが明かされる性質のものである。直接観測できるものだけで成り立つものは科学ではない。

no science would exist other than as mere data collection. ... It [=science] has powers and mechanisms which we cannot observe but which we can experience indirectly by their ability to cause---to make things happen in the world. (p.20)

Bhaskar (1978) による3つの存在論的マップ――エンピリカル vs. アクチュアル vs. リアル

A distinction can be made between three ontological domains : the empirical, the actual and the real. The empirical domain consists of what we experience, directly or indirectly. It is separated from the actual domain where events happen whether we experience them or not. What happens in the world is not the same as that which is observed. But this domain is in its turn separated from the real domain. In this domain there is also that which can produce events in the world, that which metaphorically can be called mechanisms. (p.20; my emphasis)

要するに、

- エンピリカル:経験(観測)できるもの

- アクチュアル:(経験したかどうかとは無関係に)実際に起きたこと

- リアル:出来事を生み出す力・メカニズム 1 Bhaskar は、リアリティの3つの異なるドメインを区別せず、単一のものとして扱う(伝統的な)科学知識観を「認識論的誤謬」と呼んだ。

The transitive and intransitive objects of science

科学の自動詞的次元 (intransitive) と他動詞的次元 (transitive) を区別することが重要

If we refrain from reducing questions about what is to questions about how we can know, it follows that science deals with something that is independent of science itself, and that science is fallible at any time. This means that we pay attention to the fact that science has two dimensions : an intransitive and a transitive dimension. (p.22)

区別することの意義:科学者は、研究結果やデータを産出することはできるが、メカニズムは産出できない。

科学理論は、出来事と違い、他動詞的(科学者に依存する)である。

科学的知識には二つの側面がある

This is one side of ‘ knowledge ’. The other is that knowledge is ‘ of ’ things which are not produced by men at all (p.23)

Science as practice

Knowledge, including that of science, can be seen as one instrument among others to help us deal with reality in a practical way. (p.24)

The practical relevance varies in this way, because characteristic of reality is that it is differentiated, structured and stratified---it is composed of many different levels and forms of practice. (p.25)

The relation between practice, meaning, concept and language

one of the most important tools in the search for knowledge of reality is language. (p.27)

科学共同体における相互承認による科学知識の認定

intersubjective confirmation ... We must have other people's---our fellow-subjects’---approval and permission if

The objects of natural science and of social science, respectively

事実 (facts) は、理論に依存する。

- 自然科学の対象と社会科学の対象の違い。

- 自然科学の対象は、定義は社会的に行われるが、そのもの自体は自然から生み出されたものである。

- 社会科学の対象は、定義も産出も社会的に行われる。※ただし、だからといって言語的に構築されたものというわけではなく、実在的 (real) なものである←とくにここが批判的実在論のコア。

社会科学に典型的な「二重の解釈学」(vs. 自然科学的「一重の解釈学」)

the study of social objects involves a ‘double hermeneutics’ : the social scientist's task is to ‘interpret other people's interpretations’, since other people's notions and understandings are an inseparable part of the object of study. (p.32)

概念 (concepts) の重要性:社会現象において概念といったとき、人々は単に社会についての概念(メタ的)を形成するだけでなく、その概念自体が社会現象の構成要素となる (p.33)

社会現象Xと、社会の全体性・構造との密接な相互依存関係: →貨幣を例に取るとわかりやすい。貨幣は社会的約束事という意味での構築物に過ぎないことは事実だが、(1) 構造化された社会の全体性の中で作用し、かつ、(2) この全体性は、存在の物質的側面との関係のなかで作用する。 →このことからわかるとおり、批判的実在論における言語の重視は、相対主義哲学を意味するのではなく、あくまで 他動詞的次元 vs. 自動詞的次元の区別の重視 を意味するもの。

The conditions of conceptualization within social science

研究対象の人々がした説明を、「説明」だとするなら、社会科学はいらん、 という話。――以下の of が曖昧だが、原文(スウェーデン語)を読めないのでどうしようもない。

But if the explanations of others were really the very explanation, there would be no need of social science. ... reality encompasses a not directly observable deep dimension---the level of generative mechanisms---which justifies the existence of science.(p.36)

解釈主義的アプローチへの批判 (p.37) →「社会現象には実在的次元があるんだから構築作用に還元すべきではない部分もある」云々という、本書でここまでに繰り返されてきた話。

便利な二分法 - 閉鎖システム → 一重の解釈学 → 自然科学的(あくまで「的」であることに注意) - 開放システム → 二重の解釈学 → 社会科学的

Chapter 3. Conceptual abstraction and causality

本章は、概念化 (conceptualization)・概念形成 (concpet formation) に焦点を当てる。概念化・概念形成は、社会科学におけるもっとも重要なツールの一つ。

Conceptual abstraction

抽象的なものと具体的なものとは何か。両概念は関係的・相補的なもの。抽象的なものは、具体的でないもの、つまり観測可能ではないもの、ということになる。

社会科学において概念の抽象化作業は、自然科学における実験と同等の位置にあり、その点で非常に重要である。(p.43)

リアリティの3つのドメイン(再度登場)

Reality consists of three domains : our experiences of events in the world, the events as such ( of which we only experience a fraction ) and the deep dimension where one finds the generative mechanisms producing the events in the world. (p.43)

実験ができないなら、抽象化によって、概念を別の概念から「剥離」するしかないという話。

Thus when we wish to gain knowledge about generative powers and mechanisms in social worlds, one of the most splendid tools at our disposal is the isolation of certain aspects in thought---abstraction---rather than isolating them by manipulating events. (p.43)

そして、その隔離された抽象概念はそのままでは観察不可能なものである。観察可能になるのは、リアリティに付随する影響力(メカニズムの生成力)によってリアリティが経験可能になったときのみである。

they[=abstract concpets] manifest themselves through their effects, but it is not possible to immediately observe or ‘touch’ what the concepts represent, that is, the generative mechanisms. (p.43)

適切な抽象化方法は? →必須のプロパティもあれば、重要性が低い偶然的なプロパティもある。批判的実在論は、前者、つまり「自然な必要性」に焦点化する。

Critical realist analysis is built around this understanding of natural necessity, and our abstractions should primarily aim at determining these necessary and constitutive properties in different objects, thus determining the nature of the object. (p.44)

Structural analysis

構造分析 :[前節の概念形成・抽象化の意義を受けて]nature (必須のもの) とそうでないものをわけ、異なるものをきちんと分離し、同じものをすべてまとめるという抽象。それを可能にするのが、構造分析とのこと。

社会科学での対象を分析するうえで「関係」に焦点化するのが非常に重要。「関係」には、以下に示した3種類の区別すべきポイントがある。で、1から4へ、番号が大きくなるにつれてより本質的で nature に近い必要性となる。

┌─1形式的 │ └─ 実質的 ─┬─2外在的 │ └─ 内在的─┬─3非対称的な必要性 │ └─4対称的な必要性

区別A:formal relation と substantial relation を区別し、formal existential relation ではないということで除外

Substantial relations means there are real connections between the objects, formal that there are not, but nevertheless the objects somehow share a common characteristic---they are in some respect similar. (p.45)

区別B:外在的 vs. 内在的。 AとBの関係が、一方がもう一方に依存的の場合、internal と定義する。つまり、Aが消えると、A-Bの関係が消えるため、Bも消えるような関係。一方、external な関係は、一方が消えても関係は消失しないので、重要性は低い。

区別C:対照的 vs. 非対称的 A-Bの関係が相互依存的である場合は、symmetically internal として、一方通行的な asymmetrically internal と区別する。

関係の集合→構造:(internal) relation の集合体が、社会科学の重要な(しかし、しばしば曖昧に使われる)概念である「構造」 (p.47)

Structure refers to the inner composition making each object what it is and not something else ,

構造分析の失敗 'over-extended', 'pseudo-concrete research' (p.48) その例として、例として、マルクス主義(「資本家 vs. 労働者」で多くのことを説明する)とフェミニズム (「男性 vs. 女性」で多くのことを説明する) があげられているが、もう少し説明がほしいところ。

エンピリシズム信者は、「概念は、具体的で観察可能なものと対応しているべき」という信念が強すぎる。そのため、「抽象概念は non-existence だからダメ」という無理筋な批判をする傾向がある。しかし、抽象概念は、観察可能なものの背後にあるメカニズムを解明するツールである。エンピリシズム信仰が強すぎると、こういう便利なツールを放棄してしまうことになる。(p.50)

Causality

「構造分析は必要条件だが十分条件じゃない!因果分析も必要!」という流れから、因果の話。

抽象は同時的 (synchronous/simultaneous) だから、"they cannot ... tell us anything about processes and change" (p.52) で科学的活動には記述とか計測とかいろいろあるが、、因果関係の解明は中でも最も重要な活動のひとつだと宣言2 一見すると、因果分析ってのは、自然のコントロールを向上しようとか、コントロールできなくても問題を回避するために役立てものと思われているフシがある。しかし、そういう見方は少なくとも社会科学の因果を考えるうえでは問題含みである。

What is a 'cause'?

統計分析はどこまでいっても共変関係でしかない。因果を問うことは、Yを生起・産出・生成したものが何かを問うことである。つまり、問題なのは、XとYの関連ではなく、X-Y関に働く力・傾向 (powers or liabilities) の問題である。

A cause is something totally different to statistical co-variance. To ask what has caused something is (Sayer 1992: 104) ‘to ask what “makes it happen”,what “produces”, “generates”, “creates” or “determines” it, or, more weakly, what “enables” or “leads to” it’. From a realist perspective it is not a matter of a relation between two events ... It is a matter of what causal powers or liabilities there are in a certain object or relation. In more general terms it is a matter of how objects work, or a matter of their mechanisms

因果に関する言明は、対象の本性が生み出す力、要するにメカニズムについて論じているのであって、ある出来事(結果)とその原因の間にある関連を取り扱っているわけではない。XがYを引き起こそうが引き起こすまいが、 メカニズムは実在 している。

a causal statement does not deal with regularities between distinct objects and events ( cause and effect ), but with what an object is and the things it can do by virtue of its nature. (p.55)

The objects and their structures, powers, mechanisms and tendencies

4つの概念(構造・パワー・生成メカニズム・傾向)を詳細に検討する節。

A stratified world with emergent powers and mechanisms

リダクション:集団レベルでは複雑で不明確な現象を、より小さい単位(個人など)にすることではっきりさせる

a reduction which means that a concrete compound phenomenon is decomposed into smaller and smaller components. (p.59)

When the properties of underlying strata have been combined, qualitatively new objects have come into existence, each with its own specific structures, forces, powers and mechanisms. The start of this new and unique occurrence is called emergence, and it is thus possible to say that an object has ‘emergent powers’. (p.60)

メカニズムには階層性がある。たとえば、特定の化学反応に関するメカニズムは、その上位のメカニズム――たとえば、原子間の化学結合の理論――によって説明される。

Open and closed systems

開放システムと閉鎖システムの区別。

閉鎖システムの説明:

a closed system is at hand when reality's generative mechanisms can operate in isolation and independently of other mechanisms (p.66)

要するに、リアリティの生成メカニズムが、他のメカニズムに邪魔されなければ、偶然的な諸条件に左右されることが減るため、予測可能性は高くなる。因果連鎖の環が閉じているという意味でこれは閉鎖システムといえる。 一方で、社会科学的なメカニズムはどんなものであれ、他のメカニズムから独立しているということはありえない。したがって、あるメカニズムに関する科学的説明が可能な状況だったとしても、予測可能性は低くなる。この場合、因果連鎖の環は閉じておらず、開放システムである。

システムのタイプが違うわけなので、社会科学は(自然科学と比して)説明の質が低いわけではない。